Portfolio

Throughout my career, I have contributed to diverse engineering projects across multiple industries, from automated brewing systems and industrial robotics to reliability testing for autonomous vehicles and heavy machinery. My experience spans mechanical engineering, product development, and reliability testing across various sectors. Below are some of the organizations I have collaborated with:

The following sections detail my professional experience and key contributions across these organizations.

Cruise

As a Senior Reliability Test Engineer at Cruise, I specialized in autonomous driving hardware validation, focusing primarily on compute modules and their associated components. My responsibilities included comprehensive testing of various sensor systems including lidar, radar, microphones, and cameras, as well as contributing to specialized vehicle projects for delivery and accessibility applications.

Loon

Loon developed a network of high-altitude balloons to provide LTE connectivity to underserved communities worldwide and during emergency situations.

I served as the Reliability Test Team Lead at Loon for three years, managing a team of four engineers. Our team conducted comprehensive hardware reliability testing, primarily at the component level, utilizing environmental chambers and specialized testing equipment. I was responsible for developing and executing test plans, managing a significant budget for engineering services, and ensuring the highest quality standards for our products. My role involved close collaboration with design engineers to identify potential issues early in the development process, thereby reducing costs and improving product reliability.

Loon was a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc. that provided internet access to rural and remote areas using high-altitude balloons. The company was part of Alphabet's "Other Bets" division, which included various experimental projects and subsidiaries. While at Loon, I worked on critical infrastructure that aimed to connect underserved communities worldwide.

Our team achieved a 99.9% uptime for our balloon fleet, which was crucial for maintaining consistent internet connectivity in remote areas. I led the implementation of new testing protocols that reduced product failure rates by 35% and developed automated testing systems that improved our testing efficiency by 50%. Additionally, I managed relationships with external testing vendors and oversaw the procurement of specialized equipment worth over $2 million.

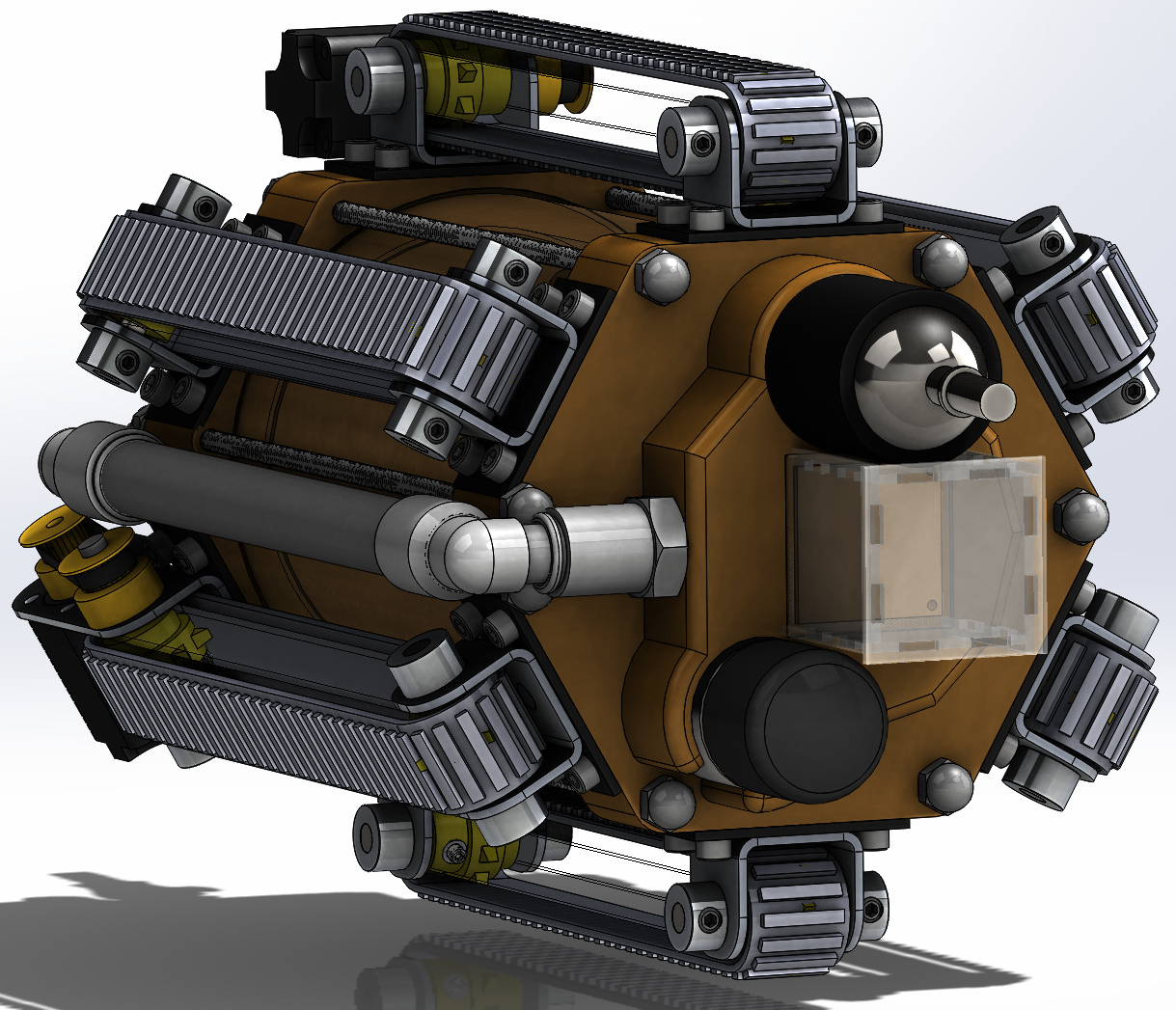

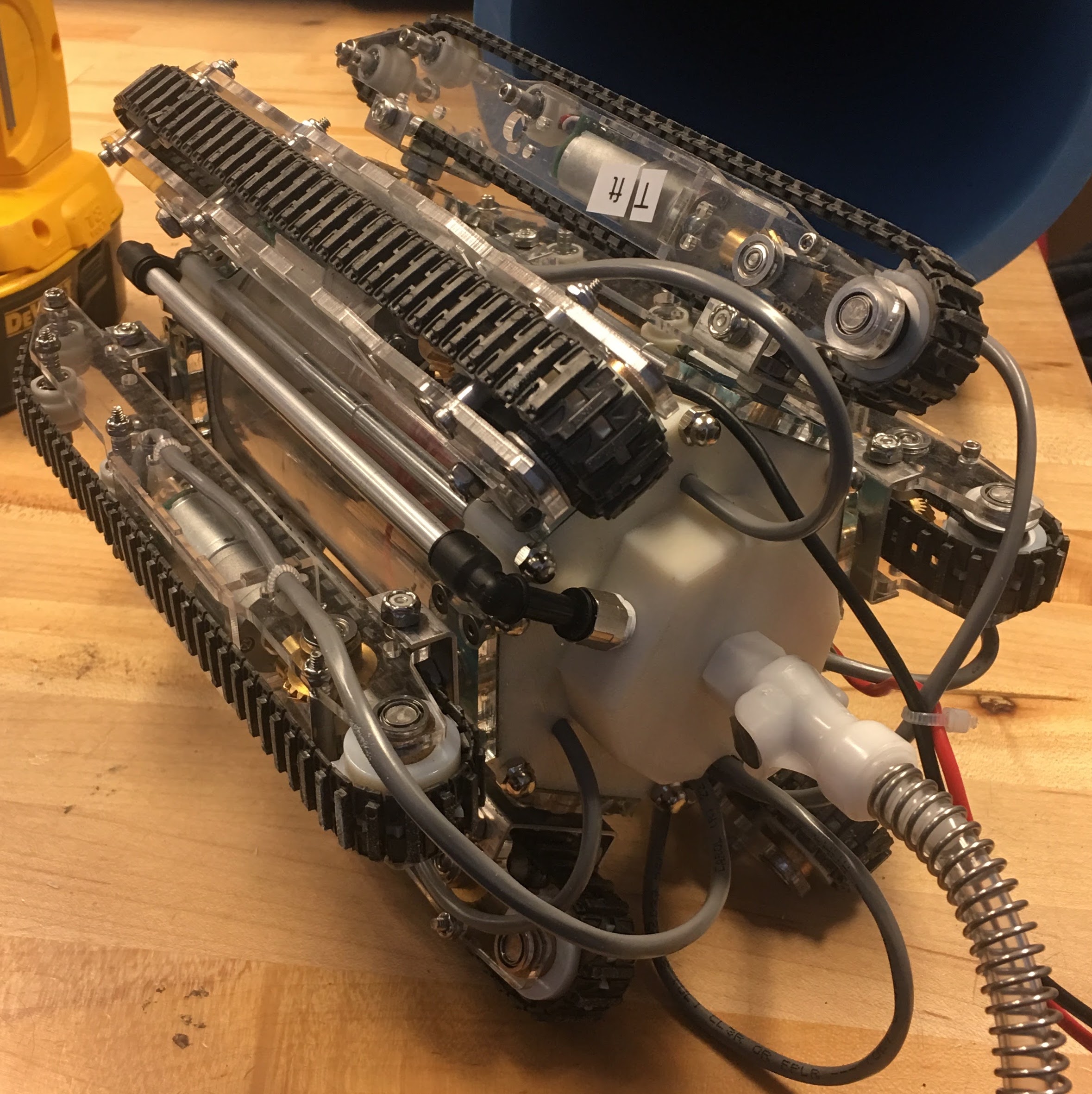

Industrial Optic

Industrial Optic was a startup I co-founded, which was subsequently acquired by Mueller in 2018. I dedicated eighteen months to developing a non-invasive solution for detecting wear on industrial machinery, leveraging image processing technology to identify maintenance needs before equipment failure. This innovation significantly reduced downtime and maintenance costs for our clients. I took the product from concept through to market deployment, securing several major contracts with Fortune 500 companies.

The technology we developed used advanced computer vision and machine learning algorithms to analyze vibration patterns and visual indicators of wear in industrial equipment. Our solution could predict equipment failures up to 3 months in advance, allowing companies to schedule maintenance during planned downtime rather than experiencing unexpected breakdowns. This predictive capability resulted in cost savings of up to 40% for our clients and improved overall equipment effectiveness.

During my time at Industrial Optic, I wore multiple hats—serving as both the technical lead and business development manager. I secured over $1.2 million in contracts and built relationships with key players in the industrial automation space. The successful acquisition by Mueller validated our technology and business model, providing a strong return for our investors and a clear path to market for our innovative solution.

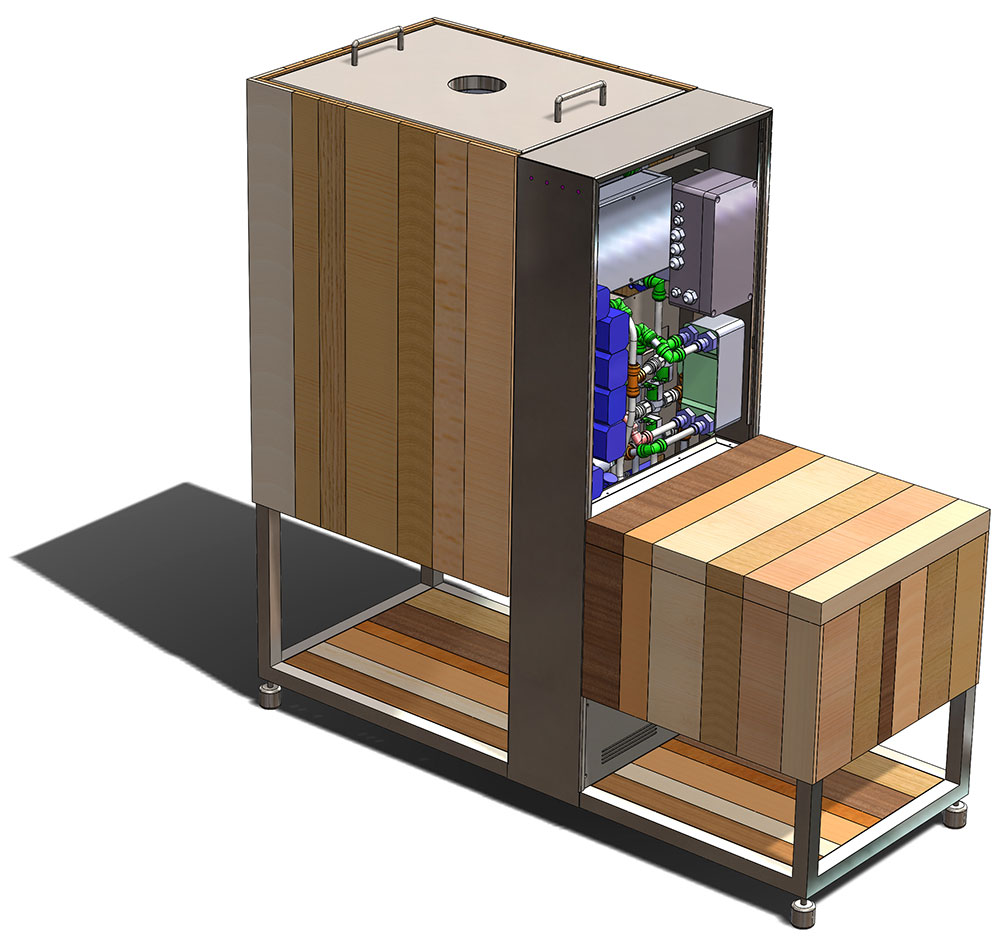

Brewbot

In 2015, I relocated to Belfast, Northern Ireland, to join Brewbot as a mechanical engineer. I contributed to the development of an automated, smartphone-controlled brewing system. Our team successfully progressed from concept to production, and I played a key role in the mechanical design, prototyping, and testing phases. This experience allowed me to work in a fast-paced startup environment while developing skills in IoT integration and consumer product development.

Modular Science

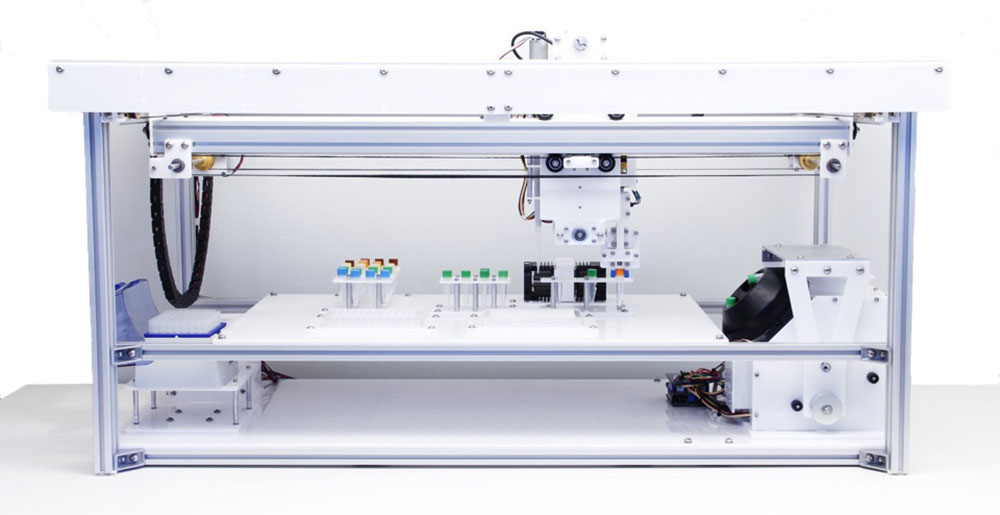

At Modular Science, I contributed to the development of a cost-effective biotech laboratory benchtop assistant, designed to provide accessible automation solutions for resource-constrained research environments. Our team employed an iterative design methodology emphasizing rapid physical prototyping over extensive CAD modeling. This approach enabled design modifications, laser cutting fabrication, assembly, and evaluation cycles to be completed within one week, significantly accelerating development timelines.

Tesla Motors

As a member of Tesla's Vehicle Test team, I conducted comprehensive testing on Model S Beta and Release Candidate vehicles. My primary responsibility involved executing full-lifetime durability assessments on pre-production units. Working alongside drivers and technicians, our team identified and documented potential reliability issues during extensive eight-month testing protocols. I contributed to meeting critical company milestones through dedicated testing efforts, including extended track testing sessions. My comprehensive 480-page test report established new standards for thoroughness within the department.

Our methodology integrated quantitative vehicle data with qualitative observations to provide comprehensive issue characterization. These findings were analyzed collaboratively with design and manufacturing teams to determine root causes and implement effective solutions.

CNH

As a Stress Test Engineer at CNH (Case New Holland), I conducted structural stress analysis on heavy construction equipment across global testing locations. My responsibilities included measuring stress responses to impacts and vibrations, and performing fatigue life assessments for various machine components. I collaborated closely with the Noise, Vibration, and Harshness (NVH) team and eventually transitioned to an NVH engineering role.

My testing protocols involved strain measurement of structural members under diverse loading conditions and comprehensive structural analysis of results. I also conducted vibration testing on electronic components, measuring acceleration responses during various operational scenarios and comparing results against specifications. Testing conditions ranged from standard operational environments to extreme scenarios, including controlled drop tests of 32-ton tractors from four-foot heights.

Zero Motorcycles

I served as a Powertrain Test Engineer at Zero Motorcycles from 2021-2022, supporting the strategic partnership between Zero and Polaris. My role involved ensuring Zero's powertrain hardware met specification requirements for integration into electrified Polaris powersports vehicles.

Additionally, my first professional role after graduate school was with Zero Motorcycles, where I began as a Production Technician assembling sub-assemblies and complete motorcycles. I quickly advanced to the mechanical engineering team, contributing to the design of the 2012 product lineup. My responsibilities included supporting senior engineers in component design, procurement, and prototype testing for production implementation.

Volunteer Engineering Work

Throughout my career, I have dedicated time to volunteer engineering work with organizations providing technical assistance for community development projects. I have traveled to El Salvador and Nicaragua on multiple occasions, contributing expertise to drinking water infrastructure projects. Both major projects focused on establishing reliable clean water distribution systems for underserved communities.

In El Salvador, as part of Engineers Without Borders - San Francisco Professionals, our team constructed a pump house, installed electrical infrastructure, and implemented an electric pump system connected to municipal water storage, providing reliable water access for the residents of San Juan de Dios. The images below document the pump house construction and final installation.

The Nicaragua project involved partnership with El Porvenir to construct a cistern for spring water storage. This system included plumbing infrastructure connecting to holding tanks and distribution to seven community faucets serving 125 residents. The system operated entirely through gravity feed, requiring no electrical components.